After the state stamped Webb Middle School, in Austin, Texas, with another failing grade, the pressure mounted to boost standardized test scores. Otherwise, the school would be closed for good. It was as if the state was pointing an angry finger at the school, shouting, “Do better … or else!”

It was a tense time, and a group of students in an after-school animation class created a film showing how they felt. In the film, students talk and laugh in the hallway, when animated monsters suddenly descend, chasing and attacking them.

The monsters are the tests.

“The message of their film was loud and clear,” recalls Allen Weeks, a longtime educator and community activist who is now executive director of Austin Voices for Education and Youth. “The kids felt they were being attacked by the tests and the system.”

That happened back in 2005, and the community fought back and won (see “How a Community Saved a ‘Failing’ School” below). But the same monster movie is now playing across the country and it rarely has a happy ending.

You can’t measure community

With little data to go on, states use standardized test scores to identify the lowest performing schools and assign grades or ranks, in accordance with federal law. If a school continues to underperform on test scores, attendance, or graduation rates, the district may take over or close the school altogether.

State rankings tell us what educators already know—schools with high populations of students of color or students from under-resourced communities sometimes do not perform well on standardized tests.

“The test scores are used to justify the closure of schools in a disproportionate way,” says Susan Lyons, principal consultant at Lyons Assessment Consulting. The rankings also distort what happens in classrooms, she adds.

“By emphasizing a single measure, we corrupt the thing we’re trying to measure, because students come to associate learning with a test score,” she says. “Schools feel pressured to organize learning around the structure and format of tests, but learning is supposed to be much richer and more engaging.”

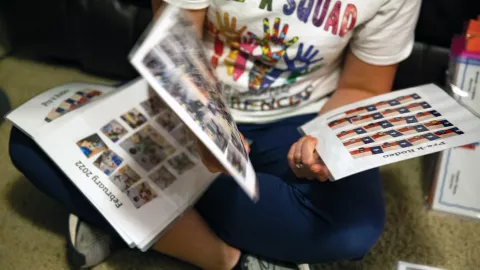

Michelle Cardenas (pictured at top), a bilingual pre-K teacher at Hillcrest Elementary School, in South Austin, says the school rankings impact her as a teacher and parent.

“I am not a fan of the letter grade,” she says. “I don’t even look at the letter for my kids’ schools.”

She has two daughters, one in middle school and the other in high school. Both schools have dual language programs, and her girls are fluent in Spanish and English. The high school has enrichment programs, like robotics and an excellent basketball team.

“The togetherness of families at basketball games is huge,” Cardenas says. “That community is very supportive. It’s a family. That’s hard to measure in a state rating.”

Her daughters like their schools and do well in their classes, yet other kids often tell them they go to the “ghetto school.”

“Their friends are transferring out to ‘A’ schools because their families think they’re better,” she says. “It tears communities apart when families flee to higher- rated schools. And the rankings don’t tell the full story of what is really happening inside a school.”

School ratings are often missing pieces of the puzzle that aren’t captured in numeric form, says Jack Schneider, an education policy analyst and professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

They don’t measure how safe and welcoming the school climate is, what arts and enrichment programs are available, the teachers’ years of experience, or the professional development available to educators.

“It tears communities apart when families flee to higher-rated schools. And the rankings don’t tell the full story of what is really happening inside a school.”

—Michelle Cardenas

Rankings increase segregation

Schools are communities of people, where students have individual strengths and weaknesses. Rankings that rely too heavily on test scores reduce them to data points.

Many families then compete for highly rated schools, driving nearby home prices ever skyward while shutting out lower income families. The result is segregation.

Research shows that increases in school segregation by race and socioeconomic status over the past 20 years can be attributed to school accountability policies, such as No Child Left Behind, Lyons points out.

“The typical person doesn’t know how schools are rated and just sees the A through F or 1 to 10, and assumes those ratings reflect what makes a good school or a bad school,” she says. “Those who have the ability to pay for housing in districts that receive better scores will often buy homes there, which in turn further stratifies our system by race and class, which is really detrimental for equity.”

GreatSchools.org is often a top return in online searches of school names. Cardenas’ elementary school received a B from the state, but a 4 out of 10 on the ratings website.

The site results don’t show that Cardenas spends hours of her own time creating scrapbooks for each of her students, or that she has been at the school for two decades, as have most of the teachers there.

“We don’t have teacher turnover here, which is rare during the shortage,” she says. “We have teachers who have been here 20 to 30 years with so much talent and experience, and students have that stability, but that doesn’t show up on the ratings.”

Cardenas’ school is predominantly Hispanic, and most families are low-income. Some people look at those demographics and decide against sending their children there.

“That makes me so upset,” she says. “Our school is so good! I have been here long enough to see my former students during the Senior Walk. Some go on to Harvard, some go on to community college. Where is that inour ratings?”

Open the doors to parents

Kimberly Reece teaches English for speakers of other languages (ESOL) at Charles Carroll Middle School, in New Carrollton, Md., where the state assigns numeric rankings. Her school ranked 42.5 out of a possible 96.5. GreatSchools.org gives the school a 4 out of 10.

“If you’re moving to a new community, especially from out of state, and you don’t know anything, there’s not much else to go on,” Reece says. “I’m a parent. I get it. But as a teacher, I know the shortcomings of these rankings.”

She recommends that educators encourage families to visit schools and sit in on a class. If a child is learning English, the family should visit an ESOL class. If the child has anxiety, the family can learn about the guidance program. They can also ask about the arts, enrichment, or sports.

“You can’t really learn about a school from a state rank,” Reece says. “If a school is genuinely good, it will show when you visit and talk to teachers and other parents.”

Her school’s soccer team is the best in Prince George’s County, and everyone goes to the games—students, parents, alumni, community members, and teachers.

“I don’t even like sports—even though I’m six feet tall and people assume I played ball. I am a total nerd, but I go to all the games,” she says. “I have students on the team, one of my students is the goalkeeper. I’m so proud of them and I go to support them. We have a very strong community. You can’t see that on a ranking.”

Cardenas agrees. She encourages educators and administrators to open their doors, let parents into the school and classrooms, and start bragging about everything the school is doing for students and their community.

“We have charter schools coming in and knocking at the kids’ doors,” she says. “We have to keep our kids enrolled or we lose them.”

She adds, “Charter schools go out and promise they’re going to send your kid to college, but if [students] don’t make the cut, they let them go.”

Reece isn’t suggesting that districts get rid of assessments altogether.

“But we need to move away from the reliance on test scores,” she says. “We need to focus more on the things rankings don’t show.”

Work Toward Better Assessments

Find out how to improve the way schools and students are assessed.

How a Community Saved a ‘Failing’ School

How a community saved a ‘failing’ school

When the state threatened to close Webb Middle School, in Austin, Texas, due to low rankings, the district had no plan to help the school. But the community refused to give up.

By organizing meetings and community conversations, they discovered that the No. 1 problem was family instability, which leads to homelessness, high mobility, and absenteeism.

The families, community activists, and community partners came up with a school improvement plan that became a community school plan. They built about 30 local partnerships to support family health, housing, job security, and enrichment opportunities as well as programs to overcome language barriers. Over time, Webb’s ranking improved—it became the top-performing Title 1 middle school in the district.

“Maintaining the community schools strategy has been key,” says Allen Weeks, who is executive director of Austin Voices for Education and Youth. “Academics work so much better when you are taking care of external factors impacting families and building those opportunities for kids.”

Community schools address the needs of the school and the community to solve problems, Weeks says. The strategy can turn around a public school that is struggling.

Despite the school’s progress, charter schools are still nipping at the Webb School’s heels.

“To get charters in, the state needs a certain percentage of failing schools to make their narrative work,” he says.

And in Texas, they keep moving the goal posts, and more schools don’t make the grade.

“According to the privatization narrative, there are too many schools with A’s and B’s, so they are raising the benchmark from 65 percent of students passing the standardized tests to 82 percent,” he says.

The big school districts in the state know the results will be bad. In Dallas, the superintendent said that the number of schools with D’s or F’s will rise from 7 to 27 with the new benchmark.

“They keep moving the standards up and up and up, but I don’t see it as trying to make schools better, because they are not providing the necessary resources for the low-ranked schools,” Weeks says.

Charter schools won’t help those students either.

“Charters cherry pick kids,” Weeks says. “They don’t want to take kids who need extra resources. Charters don’t have the refugees or the homeless or the kids with special needs.”

Those schools, he says, are set up on a franchise business model, and students and families must conform to that one-size-fits-all model or be shut out.

Community schools, on the other hand, are totally customized to the conditions of the neighborhood.

“We live in a hard world, with homelessness, issues with health care and housing affordability, class, and race,” Weeks says. “But we can have great schools if we work together to be thoughtful, positive problem-solvers.”

Take the Next Step

Want to know more about the community schools strategy?

Learn More

Active anywhere decisions impact our students.

From the School Board to the Statehouse or even the White House, ISEA members make our collective voice heard on a host of issues that impact our students, educators, and communities.

Learn more about what we're doing to improve the lives of our students, educators, and families.